AUSTIN SEVEN ENGINE REBUILD

Article kindly

reproduced from the Herefordshire A7 Club.

Part 8 - Attaching the block

& cylinder head

Part 1 – The crankcase,

camshaft, oil pump, rear main housing.

Part 2 - The

cylinder block, connecting rods and main bearings

Part 3 -

Crankshaft & con rods

Part 4 -

Main Bearings

Part 5 -

Carburettors, manifolds, clutch and fan spindle

Part 6 - Flywheel

Part 7 - Reassembly

Attaching the block:

If the crankcase has been prepared as discussed in Part

1, we can now attach the block - but first, I use a thin ‘Dremel’ type cutting

disc to make four cuts in each oil baffle and bend open the ‘wings’ just enough

to let the big-end pass through. These opened baffles are then placed in the top

of the crankcase with the small nibs sitting neatly in the crankcase recesses to

ensure they are correctly positioned. The top of the crankcase and the bottom of

the block are de-greased and a thin layer of sealant (again, I use ‘Blue

Hylomar’) applied to the outer contact areas of both items. After a few minutes

wait, the block is placed in-position and secured by firmly tightening the eight

5/16” nuts on new locking washers. I then attach my extra ‘holding-down’

brackets at the front and rear of the block as described in an earlier part.

Before fitting the pistons in the block, the rings should be rotated in their

grooves to position the gaps approximately 180 deg to the gaps in adjacent

rings. This helps to maximise compression by presenting the most difficult route

for any gasses escaping past the pistons.

‘Real’ engine builders use proprietary piston ring clamps but mine was cut from

an old tin can many years ago (see photo) and with everything liberally

lubricated and a firm grip - it works a treat. It is obviously important not

force the piston & ring assemblies into the bores because you might break a ring

but if the rings are correctly gapped and firmly clamped, they will happily

slide into position.

As each piston/rod assembly is inserted into the block, I attach its (well

lubricated) big-end to the crankshaft using new bolts and new deep self-locking

nuts (it’s difficult to fit a socket on the shallow ones), having carefully

noted the position of the rod orientation markings. The big-end nuts should next

be torqued-up to 18 lb.ft, followed by a quick check that everything rotates

smoothly. Finally, the ‘wings’ of the oil baffles can be closed whilst ensuring

they remain clear of the rods.

It is very important that the cams are properly lubricated before first starting

a new engine so I coat mine at this stage with EP 140 (back axle) oil.

Sump etc

I like to use a semi-deep aluminium sump because it

gives usefu l

additional capacity and also stiffens the engine. However, this requires a

simple modification to the oil pump bottom plate. The one shown here has a

lengthened pick-up pipe ‘silver soldered’ in position. Incidentally, very deep

sumps are available, but they make life rather difficult if you try to install

or remove the engine with the sump attached.

l

additional capacity and also stiffens the engine. However, this requires a

simple modification to the oil pump bottom plate. The one shown here has a

lengthened pick-up pipe ‘silver soldered’ in position. Incidentally, very deep

sumps are available, but they make life rather difficult if you try to install

or remove the engine with the sump attached.

The sump gauze and sump can now be fitted and this will enable the engine to sit

more comfortably on the bench.

Flywheel & clutch

Run-out has previously been checked and adjusted, so

assemble the flywheel with its woodruff key in position on tapers that are dry

and clean. Check the flywheel nut has a good thread and tidy flats - but replace

with new if in doubt – then, with a new locking tab in position apply a thin

film of medium strength thread-lock and tighten the nut very, very firmly.

Preventing the crankshaft from turning is probably most safely achieved by

placing a good sized softwood block inside a strong area of the crankcase. I

have read that a drift poking out of the flywheel rim and resting on the top

edge of the crankcase can be used to lock the crankshaft. However, I have seen

broken crankcases that look as if they have suffered from this method and

several others sporting cracks hereabouts, all of which seems to suggest that

this is probably not a great approach!

Clutch assembly and the insertion of the ‘mousetrap’ springs is very

straightforward if you have three nice long ¼” BSF bolts with nuts and washers.

A clutch plate alignment bar is also essential, I made mine in about ten minutes

from a mild steel bar many years ago and the dimensions can be found on page

A5-11 of Woodrow.

Valves & springs etc

Assembling A7 valve gear is well described in numerous books so I will

not repeat it here. However, there are one or two points perhaps worth

mentioning:

• Always use valves that are retained by cotters rather than pins

• Double valve springs (if used) should be accompanied by appropriate cotter

retainers

• ‘Flick’ the bottoms of assembled valves with a screwdriver to make sure the

cotters are fully seated before checking clearances

• Set tappet clearances at 4 thou’ for both inlet and exhaust when using a

standard A7 camshaft and this makes for a nice quiet engine. Interestingly,

Woodrow reckons 6 thou’ inlet and 7 thou’ exhaust. For sporty high lift

camshafts, use 6 thou’ inlet and 8 thou’ exhaust although this makes the engine

quite noisy at tick-over

• When adjusting tappet clearances, use the ‘sum of nine’ method. For example,

adjust one when eight is open, two when seven is open etc etc. Or you can simply

adjust the inlet and exhaust tappets when the piston of that cylinder is at TDC

on the compression stroke

Cylinder head

Carefully tighten cylinder head nuts (over flat washers) incrementally in the

recommended sequence to 18 lb.ft, this is perfectly adequate. I have seen 22

lb.ft or more suggested and I believe this figure is too high and maybe the

cause of cracks in the block around the centre stud (mentioned in Part 3 of

these notes). Blocks with re-lined bores are particularly vulnerable.

External oil filter

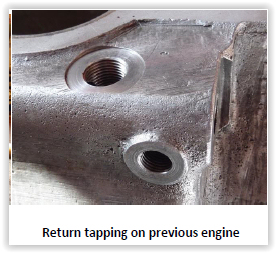

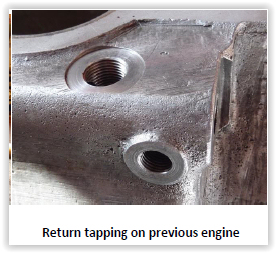

I described a full-flow external cannister type oil filter in Part 1

and the photo on the left here shows how it is connected to the engine. My spare

engine also has an external oil filter, but its return connection was drilled

and tapped (with some difficulty) into the top of the main gallery just behind

the dynamo as shown in the photo on the right. The new approach is less tidy but

definitely much easier.

Finally, it is important that dynamo bearings are in good condition and there

should be no discernible end-float. We can now set the engine timing. I do this

by removing the spark plug from No 1 cylinder and rotate the engine (using the

starting handle or by pushing the car forward in top gear) with my thumb over

the plug hole. It is then easy to detect the compression stroke and set the

distributor so that the points are about to open with the rotor arm pointing in

the direction of the No 1 HT plug lead. Thus set - the engine will invariably

fire-up and run, then when warm, I rotate the distributor anti-clockwise (viewed

from above) to advance the engine until it sounds very slightly rough, then

back-off a little. Someone once said: “Start with it very slightly advanced then

retard it bit at a time until your lap times increase”.

Well, that’s about it and I hope the reader has found these ramblings to be of

some interest

.

Spanner Article kindly reproduced from the Herefordshire A7 Club.

l

additional capacity and also stiffens the engine. However, this requires a

simple modification to the oil pump bottom plate. The one shown here has a

lengthened pick-up pipe ‘silver soldered’ in position. Incidentally, very deep

sumps are available, but they make life rather difficult if you try to install

or remove the engine with the sump attached.

l

additional capacity and also stiffens the engine. However, this requires a

simple modification to the oil pump bottom plate. The one shown here has a

lengthened pick-up pipe ‘silver soldered’ in position. Incidentally, very deep

sumps are available, but they make life rather difficult if you try to install

or remove the engine with the sump attached.