DECARBONIZING THE AUSTIN SEVEN

From the Austin Magazine 1934

DECARBONIZING the Austin Seven is a

perfectly straightforward job well within the capabilities of any keen owner.

Before dismantling the engine it is wise to disconnect the battery as a spanner

accidentally dropped on the starter terminal can otherwise cause a dangerous

short circuit. The following procedure should be followed for dismantling: —

(a) Drain the radiator by means of the tap (or, in some

cases, plug) at the base;

(b) disconnect the sparking plug leads; the high tension

terminals are numbered for correct replacement;

(c) disconnect the upper water joint by removing the single

bolt which holds the water outlet to the cylinder head, there is no need to

disturb the hose joint;

(d) disconnect the petrol pipe from the carburetter and also

from the petrol pump or, in the case of early models with a dash tank, from the

petrol tap;

(e) remove the split pin and slip out the carburetter control

rod at the carburetter end and disconnect the strangler wire;

(f) disconnect the exhaust pipe from the manifold by removing

the four bolts;

(g) undo the seven nuts which hold the combined exhaust and

inlet manifold in place and remove the manifold and carburetter complete. On

early models, incidentally, the inlet and exhaust manifolds are separate and the

inlet must be removed first;

(h) remove the 14 cylinder head nuts and lift the head and

gasket.

IF THE HEAD STICKS.

As a general rule, no trouble will be experienced with the head sticking to the

cylinder block, but should any difficulty be encountered the head may be lifted

by means of special tools screwing into the sparking plug holes or,

alternatively, the engine may be turned over by means of the starting handle

when the compression will almost certainly lift the head sufficiently to break

the joint; needless to say, the sparking plugs must be in place for this

operation.

With the head removed the combustion spaces may be

cleaned out in the usual way and the sparking plugs should, of course, be

detached and taken apart for thorough cleaning, subsequently being adjusted so

that the gap is .015 to .018 in.

Attention may then be turned to the cylinder block and the piston crowns should

be scraped clean, rag, of course, being stuffed in the bores above the two

pistons which are at the bottom of their strokes, so as to prevent carbon

chippings finding their way into the cylinders concerned whilst the other two

pistons are being dealt with.

Whether or not the valves are ground in at each

decarbonizing is a matter for the owner to decide. Some people believe in

removing the head and decarbonizing at 2,000-mile intervals, grinding in the

valves at every alternate decarbonizing. Other owners run the engine for

periods of 3,000 - 4,000 miles and attend to the valves on each occasion.

Probably the former is the better course for maintaining absolute efficiency.

TO REMOVE THE VALVES, the cover plate must be taken off and the spring compressor supplied in the tool kit should be used. The compressor, which is in the form of a clamp, should be so placed that its forked end comes underneath the valve collar whilst the screw at its opposite end engages with the centre of the valve head. By turning the screw, the spring will be compressed, so bringing the collar away from the cotter pin in the valve stem and allowing the latter to be removed by means of a pair of pliers.

On models up to and including 1934, split cone cotters

were used to retain the valve springs, these cotters fitting into a tapered

groove in the valve stem. Care must be taken not to lose them on removal as they

are rather diminutive.

When the cotters have been removed the springs can be lowered again by

unscrewing the compressor, the valves withdrawn and the springs and collars

removed. The valves are numbered, and on removal each valve should be placed

with its spring collar and cotter so that each assembly can be replaced in its

original position.

Before each valve is ground in, it is a good plan to

scrape off any carbon deposits which may have collected on the stem or head, a

job which can be done either with a stiff wire brush (a file card is excellent)

or a knife. It is also a good plan at this juncture to clean out the ports so

far as possible, and for this job a bent scraper will be found useful for

reaching round the various corners. A small wire brush may also be a help;

In passing, it is worth advising the owner also to clean out the exhaust

manifold so far as possible as it is not much use having clean ports if the

manifold is thoroughly choked with carbon.

Before grinding-in is commenced, the tappets should be

let down a turn; that is to say, their lock nuts should be slacked off and the

tappet heads screwed down. The reason, of course, is to provide extra clearance

so that there is no risk of the stems touching the tappets and thus preventing

the valve seating properly.

Grinding-in is carried out in the usual manner, a small quantity of grinding

paste being smeared round the valve face, the valve slipped back into position

and then rotated by means of a screwdriver engaged with the slot in its head. A

fair pressure should be exerted whilst the job is being done, and the valves

should be turned in a semi-rotary movement, frequently being lifted off their

seatings and turned to a fresh position. Continuous turning is inadvisable.

There is no need, incidentally, to continue grinding until the whole of the

seating and valve face are polished. Once a thin, continuous polished line

appears on both seating and face, the job may be considered done.

Subsequently the valves should be thoroughly cleaned and

all traces of grinding compound removed from the seatings and ports, whilst the

valve guides should also be cleaned, a job which can very well be done with a

small bottle brush.

Reassembly is a straightforward repetition of dismantling, except that owners

may find a little difficulty in dealing with the split cotters of early models.

The best plan is to smear a little thick grease on to the end of the valve stem

so that the cotters may virtually be stuck in position whilst the spring is

being lowered. Needless to say, the valves will have to be adjusted, a job which

is done simply by screwing the tappet head in or out until the correct

clearance is obtained, and then tightening the lock nut.

Correct tappet adjustment can be obtained only when the engine is hot, the

specified clearance being .004 in. for both inlet and exhaust. As a preliminary

setting, however, a clearance of .006 in. may be given for the inlets and .008

in. for the exhausts.

REASSEMBLY

No snags are likely to arise during subsequent reassembly of the engine after

decarbonizing, but owners are advised to have available a new cylinder head

gasket (price 2s.), a new manifold gasket (price 10d.), a new washer for the

water connection (price ld.), and a new exhaust pipe washer (price 3d.). With

care, of course, the old gaskets can often be used again, but new ones should be

on hand in case they are required. To put back a doubtful gasket is false

economy. The cylinder head gasket, by the way, should be smeared on each side

with grease.

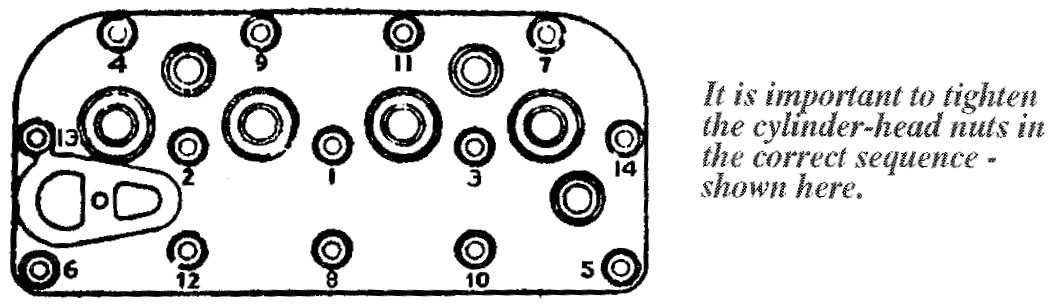

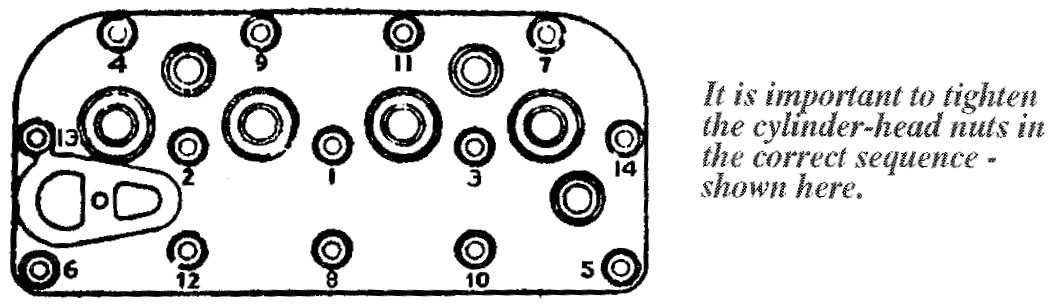

The only other point of importance concerns the cylinder head nuts, which should

be screwed up until they are finger-tight and then given their final tightening,

a turn at a time, in the order shown in one of the accompanying illustrations.

The remainder of the reassembly process calls for no comment, but it is worth mentioning that when an engine has been completely down, Austin mechanics assemble the cylinder block, valves and head as a unit on the bench instead of replacing the block separately. Owners, however, may find it easier to put back the block first and then replace the head.

The fan belt should be adjusted so that there is no visible slack, but the belt is not under tension when the engine is stationary.

A point about which owners are sometimes in doubt is the engine mounting. The crankcase is bolted to the chassis at four points and, on models up to 1934, the bolts should be kept dead tight. On subsequent models rubber washers are employed to insulate the chassis from engine vibration, and in this case the nuts should be sufficiently tight to prevent any free movement, but not so tight that the rubber washers are unduly compressed. The nuts are secured by split pins, which must be replaced if they have been disturbed. As engines increase in age, the rubber washers tend to compress somewhat, and this may be counteracted by tightening as just described. If, however, the washers are perished, there is nothing for it but to replace them.